There is a mismatch between what science knows and what business does. Science knows that the 20th century tiered financial rewards do not improve performance and can even destroy creativity.

The secret to high-performance is that unseen intrinsic drive– the drive to do things for their own sake. The drive to do things because they matter to the doer.

What science tells us from the candle problem.

Created in 1945 by a psychologist named Karl Duncker. Participants are given a candle, some thumbtacks and some matches. “Your job is to attach the candle to the wall so the wax doesn’t drip onto the table.” You time how long it takes people to find a solution.

Created in 1945 by a psychologist named Karl Duncker. Participants are given a candle, some thumbtacks and some matches. “Your job is to attach the candle to the wall so the wax doesn’t drip onto the table.” You time how long it takes people to find a solution.

How do we get the quickest solutions? The standard business model is if you want people to perform better, you reward them. Right? Bonuses, commissions, etc. Incentivize them. That’s how business works. But that’s not happening here.

The group who were offered a reward for being in the top 25% actually took 3.5 minutes longer than people who were given no reason to rush. You’ve got an incentive designed to sharpen thinking and accelerate creativity, and it does just the opposite. It dulls thinking and blocks creativity.

This experiment has been replicated over and over again for nearly 40 years. Contingent motivators — if you do this, then you get that — work in some circumstances. But for a lot of tasks, they actually either don’t work at all or, often, they do harm. This is one of the most robust findings in social science, and also one of the most ignored.

If-then rewards work really well for tasks where there is a simple set of rules and a clear destination to go to. Rewards, by their very nature, narrow our focus, concentrate the mind. So, for mechanical tasks a narrow focus, where you just see the goal right there, zoom straight ahead to it, incentives work really well.

But for the candle problem, you want to be scanning wide. The solution is on the periphery. But rewards actually narrow our focus and restricts our creativity.

In the 21st century, white-collar workers are doing less of that routine, rule-based, left-brain work. That work is easy to outsource and fairly easy to automate. So what really matters are the more right-brained creative, conceptual kinds of abilities. Even in purely manual labour jobs, eg road repair, if some judgement and discretion remain then incentives don’t improve the quality of individual output.

In the 21st century, white-collar workers are doing less of that routine, rule-based, left-brain work. That work is easy to outsource and fairly easy to automate. So what really matters are the more right-brained creative, conceptual kinds of abilities. Even in purely manual labour jobs, eg road repair, if some judgement and discretion remain then incentives don’t improve the quality of individual output.

Another experiment conducted in 2005 by Dan Ariely and three colleagues with MIT students. They gave the MIT students a bunch of games that involved creativity, motor skills, and concentration. And then offered them, for performance, three levels of rewards: small reward, medium reward, large reward. To avoid cultural bias they later repeated the experiment in India.

What happened? As long as the task involved only mechanical skill bonuses worked as they would be expected: the higher the pay, the better the performance. Okay? But once the task called for even rudimentary cognitive skill, a larger reward led to poorer performance.

HIGHER INCENTIVES LED TO WORSE PERFORMANCE.

That is what happens in experiments. What happens in the reality. In 2009 Economists at the London School of Economics looked at 51 studies of pay-for-performance plans, inside of companies. Here’s what they said: “We find that financial incentives can result in a negative impact on overall performance.”

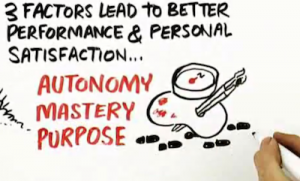

The good news is that the scientists who’ve been studying motivation have given us this new approach. It’s built much more around intrinsic motivation. Around the desire to do things because they matter because we like it, they’re interesting, or part of something important.

This new operating system for our businesses revolves around three elements:

Autonomy: the urge to direct our own lives.

Mastery: the desire to get better and better at something that matters.

Purpose: the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves.

These are the building blocks of an entirely new operating system for our businesses.

Let’s consider autonomy in some detail. Traditional notions of management are great if you want compliance. But if you want engagement then self-direction works better.

Consider examples of some radical notions of self-direction. This requires paying people adequately and fairly, absolutely getting the issue of money off the table, and then giving people lots of autonomy.

Let me give you a radical example of it: something called the Results Only Work Environment (the ROWE), created by two American consultants, in place at a dozen companies around North America. In a ROWE, people don’t have schedules. They show up when they want. They don’t have to be in the office at a certain time, or anytime. They just have to get their work done. How they do it, when they do it, where they do it, is totally up to them. Meetings in these kinds of environments are optional.

What happens? Almost across the board, productivity goes up, worker engagement goes up, worker satisfaction goes up, turnover goes down. Autonomy, mastery and purpose, the building blocks of a new way of doing things.

Let’s look at a real life example where incentives don’t work as well as autonomy. In the mid-1990s, Microsoft started an encyclopaedia called Encarta. They had deployed all the right incentives, they paid professionals to write and edit thousands of articles. Well-compensated managers oversaw the whole thing to make sure it came in on budget and on time. A few years later, another encyclopaedia got started with a different model. Do it for fun. No one gets paid a cent. Do it because you like to do it.

Who would have predicted the Wikipedia model would become the dominant world provider and Encarta was withdrawn in 2009 from sale?

Intrinsic motivators versus extrinsic motivators. Autonomy, mastery and purpose, versus carrot and sticks, and who wins? Intrinsic motivation, autonomy, mastery and purpose, in a knockout.

For the full presentation go to https://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_on_motivation?language=en